Spring Morning, Paris

It is still early. A clean morning: a walk along the canal de St Martin to the Gare de Lyon appeals much more than taking the Metro, and meets only minimal, even token, resistance from My Lady Of The Needles. For it is one of those late winter mornings which promises delight to all the senses, touch, taste, smell, hearing, and sight, a morning when the senses play a polyphony of experience into consciousness, greater than the sum of the parts. The play of light on streets wet from last night’s heavy rain…the smell of coffee… a gull crying the call of my coastal childhood… this is a morning, a light, the Impressionists would have enjoyed.

A Day Off

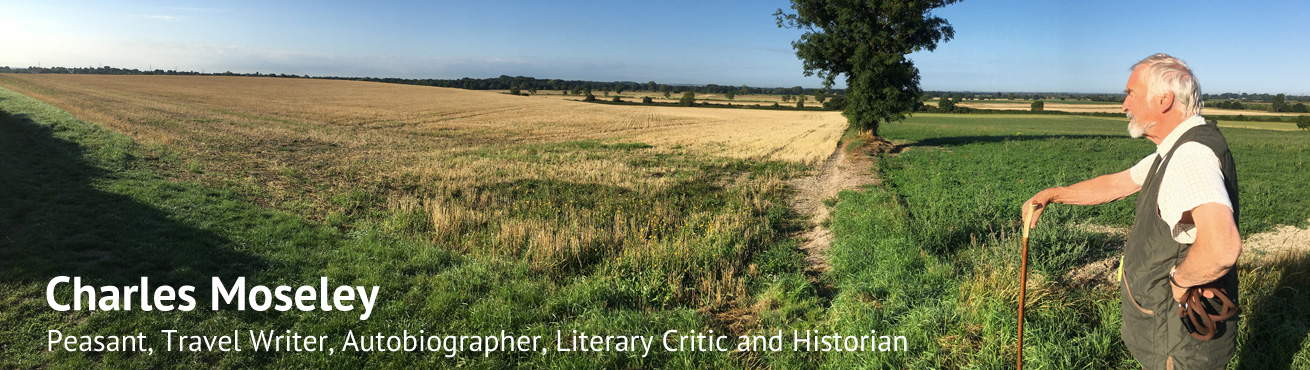

A couple of weeks ago (before everyone decided it was spring …), sharp, bright, with a hard frost, we had a day off. We woke later than usual, which, conscience quiet, gave a sense of holiday. We decided we would walk down to the washes of the Cam, for when I had driven past at sunset a few days before the water they hold in winter was covered with flocks of migrant waterfowl – pintail, pochard, tufted duck, widgeon, and the geese I love. (I have reservations about the aggressive and invasive Canadas, to be sure, but the pinkfeets and the greylags are always welcome visitors back from the far, far north.) I stopped the engine, and the quiet sunset was filled with the whistle of widgeon, the indignation of mallard, and the parleying of geese. Worth coming back to listen and see properly, I thought.

Mindworms

Mindworms

Those who know me say my mind works oddly. I suppose so. Come inside for a minute.

I suppose it was going last week to the Anglo Saxon exhibition at the British Library that did it, but I have been unable to get Beowulf out of my head for the last few days. You could pick up an earphone and hear those so well-known lines as you looked at that manuscript miraculously preserved, though singed, from the disastrous fire in Sir Robert Cotton’s Library in 1731. What else was lost from that salvage job on what had already escaped the carnage wrought by Reformation, neglect and ignorance? Was Beowulf not the only great epic poem reaching back to the dawn of the England we take for granted, perhaps not even the best? We shall never now know. But hearing those lines gave me a feeling once more (and never forgotten since it first happened decades ago) of something stirring in the deep past, something that somehow I knew, shared. The sound of the speech sits easy on my ear, the pattern of verse comes naturally to the rhythm of my tongue.

‘Dreich’

‘Dreich’: the word Rosanna used as we opened the curtains this late January morning was perfect: the Scots expresses the dourness, the glumness, the greyness of a day that is neither cold nor warm, just dull, still, sitting on your spirits, with even the woodpigeons not bothering to tell each other, ‘My toe hurts, Betty!’ I chose not to go down the Fen on a doolie day like this for my pre-breakfast walk, and so set off up what they call a hill round here – though to a man brought up in sight of the fells and moorlands up north the word does still seem optimistic. Still, from its 35 foot summit you can see for miles – at least, you can on a clear day – even to the tower of Cambridge University Library, and Addenbrooke’s hospital, and Ely Cathedral. But not on a day like this.

Going up the track with the lime and chestnut trees on one hand and Michael’s new yew hedge (growing nicely now) on the other, it was so hard not once again to grieve for dear Hector the Labrador, who would always choose this start to his busy walk if I gave him the choice. I do miss that tail waving a few paces ahead, and the important look on his face as he chose the place for his first squat. There has not been a lot of rain, but the slight frost is coming out of the marly ground, and where a tractor has run along – Andrew, I guess, going up to see to his portly Dexters – the soil is sticky. I get into a nice rhythm in the wood, which is ideal for going into deep thought and a sort of half-awareness of one’s context. I find that useful when I am trying to sort out an intractable problem. The one that preoccupies me at the moment, almost obsessively, is how to structure the new book I am writing, what to call it, how to focus its themes. My agents, A. M. Heath, who have handled three books of mine, say they love the writing but it crosses so many marketing categories they will have difficulty getting a publisher to take it. (I quoted to Bill what old Mr Bertram Foyle said to me the first day I joined his publishing firm: ‘Forget all that fine writing, dear boy, just remember that books have to sell, just like frozen peas. Your poor wife can’t buy nice clothes on fine writing.’ Bill nodded, sadly.) As the book is at present, it’s a travelogue, a memoir of many things, place and people, a pilgrimage of sorts to some sort of acceptance of what we are as humans: both the glorious and the vicious are in each and every one of us. It goes from the amphitheatres of Rome to the gulags and the Holocaust – via the glory of Bach, the vision of Dante, the wisdom of Plato and Gothic arches aspiring to the uncreated light – and the fellowship and friendliness of food shared by a southern sea, and wine pressed on a guest who did not share their language and was born of their ancient enemy, in a little gasthof somewhere near Dachau.

Iona is one of those in-between, ‘thin’, places

I am very new to this game: this is the first blogpost I have ever written. I don’t even do Facebook. So how do I begin?

Well, let me share with you some thoughts about a recent trip. They may form part, eventually, of the book I am struggling to write at the moment – never let anyone tell you that writing is an easy job, for it ain’t. We went to Iona: both of us had been before, and had found it a strangely quieting yet at the same time disturbing place – disturbing of the usual assumptions and imperatives with which one lives.

Iona is of those in-between, ‘thin’, places – indeed, it was of this very place that George MacLeod first used that expression. Between the tumultuous highway of the Atlantic and the wild solidity of Mull, between then and now (for ‘then’ is never far away), between knowing and unknowing… The Abbey church is far unlike the Celtic church that once was here: the community was refounded as Benedictine by Ranald, son of Somerled, Lord of the Isles, in the 1200s, and its worked stones and arches speak of France, of Rome, and remind of the argument lost at Whitby. His sister Beathag founded the Augustinian nunnery down the lane, and was its first prioress. (I have been to the island in the loch on Islay brother and sister called home once.)

The men running the little Calmac ferry from Fionnphort to the island must have one of the most boring jobs in one of the most beautiful places in west Scotland – though the fast currents and rips in the sound can be tricky. Ten minutes to the holy place, with a whiff of diesel and hot engine. And back again. And so on. But then, Charon must also have got fed up with all those short journeys across the Styx, and been irritated by all those passengers, shades, waiting for the next ferry to another world, stretching out their hands imploringly in their desire for the other shore. ‘Wait for the next boat!’ he grumpily calls, as he fends them off with his oar. Ten minutes back and forth, all day, across the little sound, where in the shallows of the clear water sea anemones wave their florid tentacles for passing food and urchins make their slow progress across the rocks. A canny otter is regularly seen waiting near where the fishermen sometimes gut their fish. Gulls glide by on stiff wings, watchful, and in season delicate terns shriek their harsh Norse name ‘kria’, flutter, and dive for little fish. The air smells salt. To port we can see the sunlight on the bay where in 806 a Viking raiding party massacred 68 of the monks. This bright place too has seen the darkness. This has been one of the fulchra of the world. It does not forget it. Maybe it still is. Will be.