Frustrated – The Author’s Lament

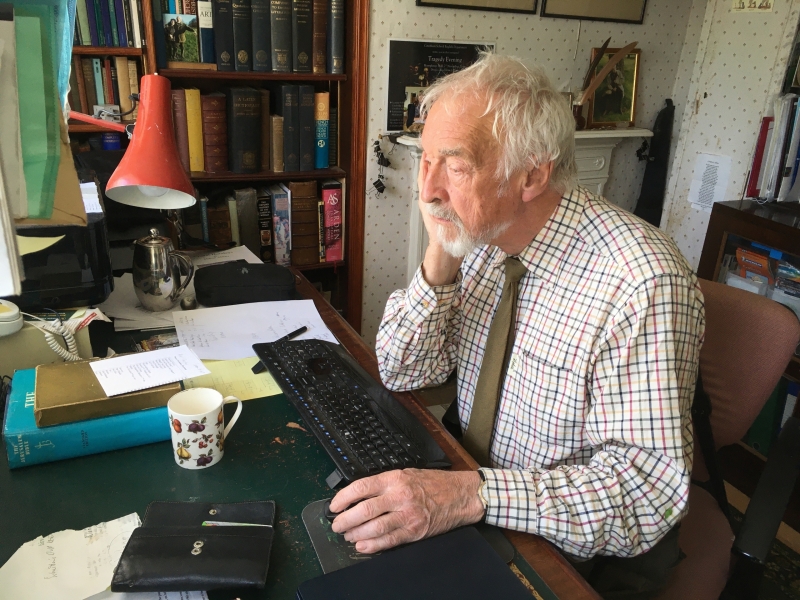

Frustrated, annoyed, miserable, grumpy. It’s a job I hate. I’m just finishing reading the proofs of my 22nd book, Hungry Heart Roaming: An Odyssey of Sorts. I’m at the stage when I am deeply dissatisfied with what I’ve written, but it can’t now be changed. Even looking out of the study window at the garden I’ve made over the years doesn’t improve my mood.

Someone who thinks as I do once said to me about his own book, ‘The Book of Proverbs says “a dog returns to his vomit, so a fool repeats his folly” but reading proofs is more like the vomit returning to the dog.’ That was long ago, in the days of long trails of paper galley proofs flooding the floor like ectoplasm: Robert said, ‘I am just a galley slave.’

An annoying restlessness in me makes me impatient with all those fiddly, necessary, things that turn what I’ve sent off to the publisher into a book – ‘yes, yes … but that’s all done with now’ – and I’m even more impatient with the business of promoting it. But, in writing about these two books, the one that will appear in the Autumn (Covid-19 willing, they say!) and the one that’s still in gestation, I suppose I’m indeed doing a sort of promotion. So while we’re at it – though it’s rather hard to go against one’s grain – do you know my Coming to Terms: Cambridge In and Out (2017), Latitude North, (2015), and Between the Tides: A Lancashire Youth (2014)? Have a look at the reviews on Amazon. But if you do decide to get them, kindly consider getting them from the publisher’s website, which is also kinder to the publisher, and to me. Even better, so My Lady of the Needles tells me, is to suggest one of them for reading by your (now) Zoomed book group. I could even be persuaded to join, as ‘The Author’ …

But as I was saying before I interrupted myself: if anyone ever tells you that writing’s an easy job, don’t believe them. Don’t think it yourself. It ain’t: it may be something you can’t stop, that’s addictive, but it’s hard graft, head down anti-socially at the desk, and even at the best of times poorly rewarded, unless of course you’re one of the few very lucky ones. And, as we all know, success breeds success. For most of us who scribble, finding a publisher, even if you have one pretty house-trained and on Christian name terms, who’ll risk money on what you’ve done – well, they get wary, and say how hard times are, and they do like to play safe. I was one myself, once upon a time, and the first day I was in the office the MD said to me, ‘Forget about fine writing, dear boy. That won’t buy your wife a new hat [well it was 1964]. Books are just like frozen peas: they have to meet what people want and expect, and sell.’ And being a nice chap I took on a few duds in my time that I thought were good – they were – and got my knuckles rapped.

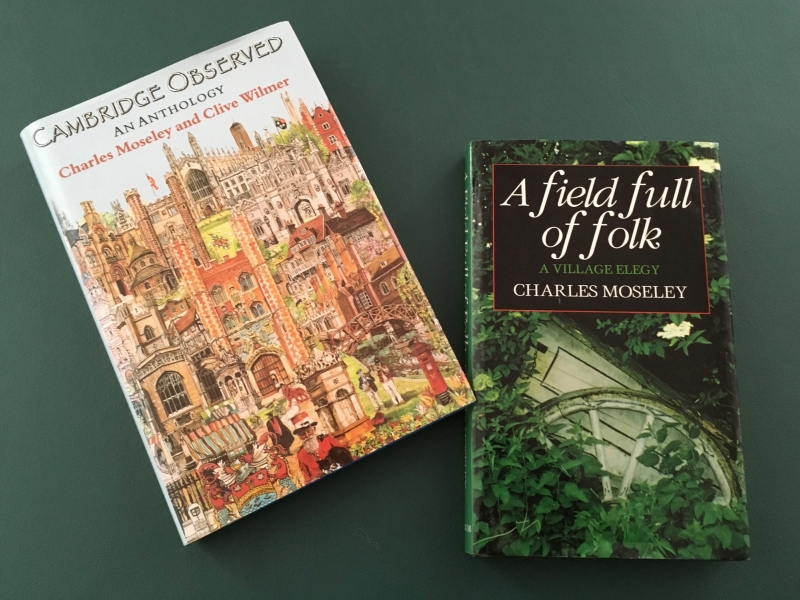

But if writing’s an itch you have, you can’t not scratch. I suppose I’ve been lucky. Pretty much everything I’ve written has found its way into print in one way or another, so far. But writing academic books and papers, while demanding and fun in its own way, isn’t the same as bringing to birth those brainchildren you really care about. Even there I can’t really complain, for so far my own non-academic books, starting with A Field Full of Folk, (1995), then Cambridge Observed (1998, co-written with Clive Wilmer), then all the others found publishers and all had very good reviews.

But it’s hard going. The first letter I had from Bill, my agent, about my Hungry Heart Roaming, which had already cost me much work and far more emotional involvement than I would have thought possible, was not great news. Those who had seen what there then was of it had said it was the best thing I’d ever done. But it doesn’t fit any particular genre, and there lay the problem, as Bill said. Mainstream publishing, to my mind to its great impoverishment, is programmed to play safe: the well known, the expected genre, the usual formula, the regular trope. For sure, that sells all right. But it’s when people break the mould and take risks and cross genres and upset expectations – in other words think outside their usual box – that interesting things happen. We’re far too stuck in the comfortable: perhaps we might have to get out of that habit as the full consequences of the Coronavirus become apparent. It’s the same with peer review in scholarly journal publication. Had there been peer review in the 1700s Priestley would never have had his work on Oxygen published and we would still be talking about Phlogiston.

More in a minute. Let me tell you about the book. Originally it was called A Time to Come Clean, for My Lady of the Needles (who’s in it, like Hector the

Labrador) told me it was time for me to come out from behind my entrenched lecture notes and my parapet of references and go over the top to – well, come clean, to say what really matters to me. Then I called it A Book of Murmurations after the ruling metaphor of the autumn starlings that swoop and swirl and dive and dance over the winter Fen beyond this house.

In the end the half quotation from Tennyson’s Ulysses fitted beautifully, for my journey is to an unknown end (and, furthermore, My Lady tells me that Bruce Springsteen afficionados will like it – but I wouldn’t know about that). My book maps a passage between two ‘in-between’ places, from one beach, in the Lancashire of my youth, at the turn of the tide, and a very young me with my grandmother, to another beach, another in-between place, with my grandson and me. In between, experience and recall of many places – and places keep their own memory, dark as often as bright, rather as clothes keep the odour of someone who wore them, or the handle of a tool remembers the smoothing of the palms that held it. (That’s one of the reasons why I love working with old tools, like old Seth’s hammers or my father’s spade.)

Places dimly hold feelings, and passions. The Swedish poet Tomas Tranströmer put his finger on it for me: ‘Time is not a straight line, it’s a labyrinth. Press your ear up against the wall at the right place, and you can hear footsteps, voices, even yourself moving about on the other side.’ In the end writing the book, trying to make sense of what I thought I knew, came to be a pilgrimage to unexpected goals: to the risk of faith, perhaps, and to celebrate the mystery and paradox of simply being human. So I describe a Greece of half a century ago, when my first, late, love and I could walk an empty road to an unknown place called Georgioupolis, where the sweet water of the mountains flowed down to the sea by a café and three dusty houses shaded by eucalyptus trees, and the beach beyond stretched for miles, deserted. Our world was young, an overture. Later, with far more baggage, came a walk alone across England, a journey to the Virgin Islands, where the ghosts of those who were there before the ships of Columbus came are not still. And then, unfinished, to the Heartland – in every sense – of Europe.

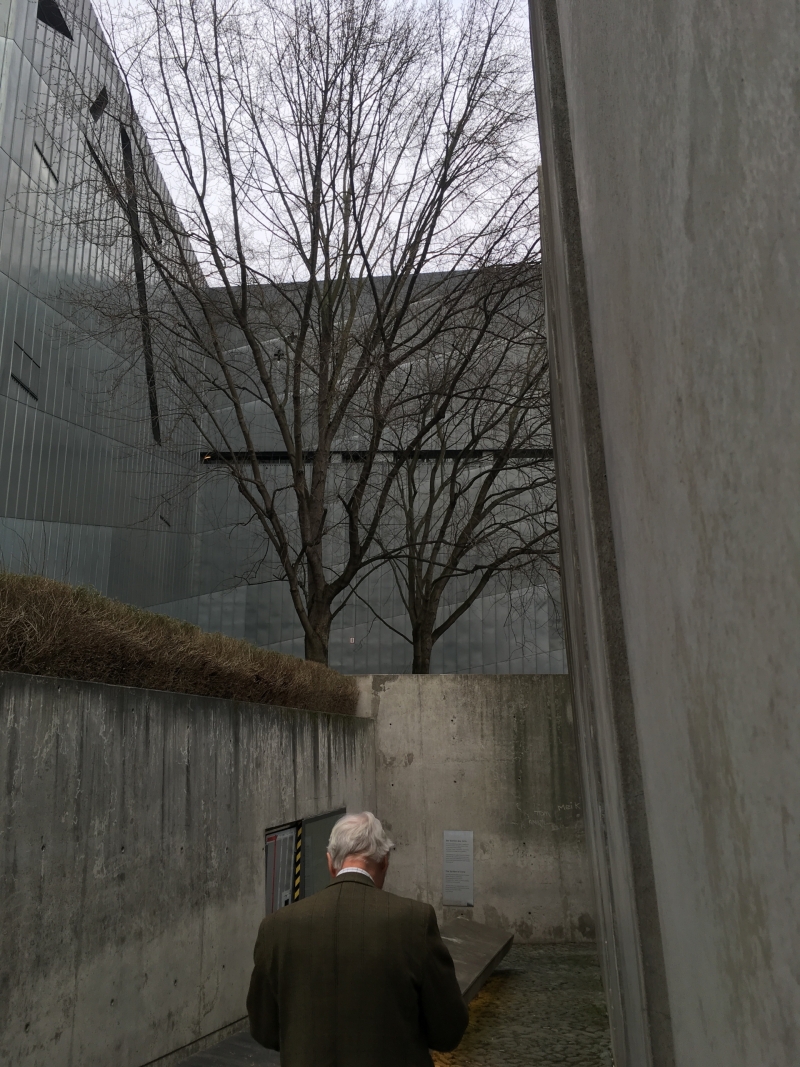

The old stories saw the Fall of Troy as the start of European history; for us the Fall of Berlin after the psychotic years 1933-45 is also another beginning. Nothing can be the same again after that industrialisation of murder.

But, like Dante emerging with Virgil from the underworld, my later love, my Lady of the Needles, and I came out of the shades of the U-Bahn that had brought us back from the Jewish Museum in Berlin – she lost relatives in

Theresienstadt – to see the stars, the stars that had shone in the clear sky of Greece and flame in the Autumn sky above Columba’s Iona.

Iona – my love’s and my place of silent time, where we seek not answers, but the right questions (and the place we dream of returning to when released from this lockdown).

I care about this book and I’m getting carried away, and forgetting I was telling you about that letter which cut me down to size. Several of my friends had seen an early draft of the manuscript, and – well, I had glowing responses from a former Archbishop, a former head of a major charity that owns a lot of England, from a distinguished radio producer who said the book was ‘marvellous’, from three professors and a major poet. So, emboldened and very pleased with myself, I had sent it off to Bill: who loved it. But then came the blow: ‘Anyone would love the wonderful writing, and the range and sophistication, but… if you were famous the new book would be lapped up… as it is…’ Well, I’m not famous, and not sure I want to be, but, like so many, many others, I am trapped in my own obscurity. You can have more if you already have much… Didn’t someone once say something like that? I grieve for all those other people over the commercial centuries, whose unique voices mapping their private journeys are unheard for ever. Perhaps it doesn’t matter. But we all want to tell our story. And I did, in the end, find a publisher. Well, there it is. Grumble and grump. But, I tell myself, and mean it: I’ve been very lucky so far in my publishers and my readers. This book might have had to be put in the bottom drawer for my heirs and assigns to empty and take its contents off to the dump. But it IS actually coming out (although, alas, frustration continues because deadlines aren’t what they used to be, pre Coronavirus, are they? And my lovely plans for launches with friends, family, colleagues and assembled illustrious ones may, like everything else, end up being virtually Zoomed). And then I can sit back…although … hang on, I’ve had an idea…. What about a book on English weather? Call it Weathering it: A Very English Obsession, 12 chapters, one per month, roughly 60,000 words, with 12 pictures by my lovely and very talented assistant (can you hear her hissing?), the Lady with the Needles whom you’ve met in my other blogs… I must talk to Bill, poor devil. Isn’t this where we came in?