Extract from Between the Tides

Here about the beach I wandered, nourishing a youth sublime,

Here about the beach I wandered, nourishing a youth sublime,

With the fairy tales of Science, and the long result of Time

Locksley Hall 1.11

I did not know any Tennyson, or Shakespeare, then, of course, but those lines, as they say, hit the spot.

The sea and the beach were never far from the mind of anyone I knew. It was amenity — it was why the town was there. At Fleetwood, it was employment, for the fishing dominated the town. It was (to a child) wilderness. And it could be tricksy, frightening even. On a quiet summer day the tide would turn and slyly creep in, encircling the sandbanks before you knew where you were. I was always being warned about ‘getting cut off by the tide’. It did happen to some people, though not so far as I know with any serious consequences, for the intervening channels were pretty shallow: people simply got wet. But Mum and Dad used to warn the visitors about the tide if they were going to the beach, and I recall one couple who at low water on a breathlessly still summer day went swimming — well, walked far out on that only slightly shelving beach into the water to try to find enough depth to swim — and when they gave up found their shoes floating like little boats in the ripples and their clothes drifting along the shore.

The tide could lie, on a still, early summer morning, in the pellucid light that you get in that west, looking as peaceful as a cat being luxuriously and sensuously stroked. But it had claws: in even a minor gale it could be awesome: you could not get away from the noise, which was everywhere, you smelt the salt two miles inland, the foaming crashing grey-brown waves threw big stones onto the promenade, and even, in 1953, could carry huge blocks of concrete away and partially flood the fields where Rossall’s cattle grazed in summer.

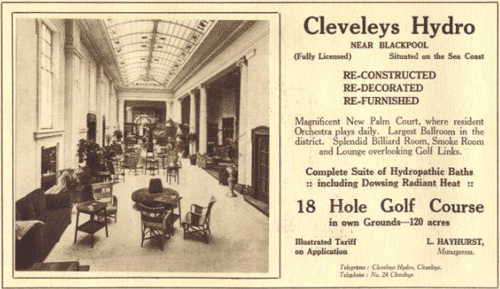

My mother remembered that in the Great Flood of 1927, when she had been working at the smart Cleveleys Hydro [Hydropathic] Hotel (now long demolished) on the higher land towards Anchorsholme the sea had breached the defences and the whole plain had been flooded for days, draining only slowly into the river. I am never sure whether she was or was not pulling my little leg when she said there were fish in the hedges as far as Thornton two miles inland. But as a child I believed her implicitly, and once, another big storm when I would have been about eight brought the sea up through the road drains, and I was disappointed not to see fish in the gutters of our road: it could not have been a properstorm…

That flat beach had very definite zones which I knew so well I could have recognized them blindfold. The storm beach, rounded stones and blown sand, and the dessicated jetsam of past high tides, was where most people picnicked, with enjoyment, their backs against the concave concrete of the sea wall. Sand scuffed into their sandwiches, and got into hair, and eyes, and into tea poured from flasks. They dropped their change out of the pockets of their wide trousers for small boys to find. They sometimes slept, turning gradually pinker in the sun, with a cooling breeze rarely absent to postpone discomfort. Their children tried to build castles in the dry sand of the storm beach, and had to go down the slope, beyond the high tide mark, to find the wetter stuff that would stand until it too dried and crumbled in the wind. But an inch or two down in that coarse sand they would hit the fist—sized round bits of glacial debris that made up the substratum of the beach, and be tempted further, yet further, down to where the backwash had scooped out a hollow parallel to the wall, and beyond that lay the long banks of good building sand. Once I too was a connoisseur, and found you could do great things with that limy sand. I had seen a picture of an unpronounceable (then) place called Neuchwandstein, and it was my ambition to recreate it in sand… (Even Ludwig never tried that!) I got a fair way, quite often, but sometimes a dog would come and squat on the topmost turret, or once a big boy came and stamped on it and I cried — but as I was alone nobody came to help. And sometimes the sea caught up with me before I could finish its defending moat, and I watched all I had made crumble into nothing but a swirl in the water.

Wooden groynes reached out into the sea in an attempt to stop the longshore drift, south to north, that carried off the beach sand, and filled the dredged channel at Fleetwood. On their lower timbers dark green weed luxuriated, which smelt rich and salty. Three, sometimes four, long banks lay parallel — still do — to the shore with hollows, sometimes mud-filled, sometimes water-filled, between them, and often deep pools where the turbulence round the end of the groynes had excavated the sand. As soon as you crossed the first bank, you left behind pretty well all the people, and entered a temporary land where the gulls gathered to rest on the drying slopes and lazily flapped away as you approached, where tubeworm cases, crusted with broken shell, felt rough to bare feet, where the lugworms and the cockles lived, and in the pools swarms of little brown shrimps darted and little green shore crabs lay half buried in the sand. Streams drained these pools across the beach, and to build a dam to hold the flow required planning, a lot of effort, and some sense of hydraulic engineering. (Far too important to let your children do it… they have to be shown how.) But out on a beach at low tide you are in a wilderness, a place untamed, however much concrete and neon are at its back and temporary dams plot its surface. Sometimes, after a very big storm, the sand would be scoured from whole parts of the beach into the Lune Deeps — more work for the bucket dredger I had loved to watch as a small child at Fleetwood — revealing a mass of boulder clay, or the trunks of the buried forest, with piddock holes in the rotting wood. At first, it was just, well, there, and nobody ever said anything about it to me, and I wonder how many people who lived with half a mile of it actually even knew it wasthere. Then an older I began to realise that once this had been dry land, that the old story about the Rossall Hall of Cardinal Allen standing a mile to seaward really did mean that the sea was eating up the land bit by bit, and I thought that these had been the woods that had surrounded the Hall. Of course, they were not, for they are much older. But my mind was usually on other urgent things. For this was where I regressed to being a hunter gatherer, like the men who had hunted in those woods, and to me the beach was my riches, my infinite room, where I dug worms, set my nightlines, fished with my clumsy rod at high tide (when older, at night with a guttering hurricane lamp beside me), and looked out for what the sea might cast up from its capaciousness. When we first went to Cleveleys and I was given the run of the fields and beach — no mobile phones then to call for help, all alone, and I came to no harm. Nor did any other kid for all I ever knew. Dad had asked Mr Matthews nearby to make me a cart out of two old pram wheels and a large green wooden box. For he found me struggling in at the gate with a large piece of wood I could hardly carry which I had found on the beach: fine firewood, and my acquisitive instincts might as well be harnessed. That cart was a godsend for years. I carted loads of firewood and kindling home, and combed the high water mark for bits of rope, and wood, and useful things people no longer wanted. Once I found a life line case for the Argentine Navy —someone translated the Spanish for me — of which I was very proud. Soon the garden became cluttered with rubbish, and an embargo was put on anything that could not be burnt. But there was one luminous summer evening — I was about 13 — when Dad was the first to break his own rule. I had been down at low tide to get any fish off my nightline and to bait and set it afresh, and in consolation for having no fish at all on the hundred hooks found the beach covered with gasping young herring, trapped in the shallows by the receding tide — perhaps driven ashore by a school of porpoises. I ran home with a stitch in my side to tell Mum and Dad the news, and Dad, moving faster than I had seen him do for a long time, commandeered my cart and made his way up to the beach and out to the water’s edge. We must have gathered at least a couple of stone, their silver sides flashing in the last of the sun, and as the sky darkened little flashes of phosphorescence glittered from the cart. Dad and Mum loved pickled herring, and that lot kept them going for quite a time. Once, after a big storm, I found a blue black lobster on the beach at Rossall, and put it, despite its slowly waving claws, in my bag and took it home. My father delighted in such things, and God bless him, ate the lot. So I never found out I liked lobster.

Porpoises themselves came ashore, poor things, and died of sunburn. One summer morning I went down as usual very early to tend my line, and found a porpoise beached about ten yards from the receding tide. It was alive, but helpless. So I took off my boots, and trousers, and just managed to lift the beast. Holding it tight to my chest I waded out into the summer sea, which fortunately was calm, sending playful wavelets over my underpants. I could see the beast’s eye, looking into mine. Could it see me, know what I was? How did its big brain deal with what was happening? It exhaled, and the hot fishy vapour came into my face. When I was waist deep, I let it down into the water, and held it, suddenly weightless. Its tail flapped, and its flippers found their old element. I let go. I said ‘goodbye’ as I did. The porpoise swan once right round me, and then out to sea. I felt very quiet when I was going home, and many people thought I was making it all up. ‘He has a very vivid imagination’, Mum used to say, as I ground my teeth. Does it sound any truer now I have written it?

Another porpoise was not so lucky. Like the first one, it was beached on a perfect summer morning. But the gulls were round it, and I could see it was dead from a hundred yards away. About a mile off a man was walking towards Blackpool. The sand was red. Someone —that man? — had disembowelled it, one long cut right up the belly cavity. The gulls returned exulting as bleakly I turned north to wait for my nightline coming out of the sea — I was earlier than usual, for of late people had been stealing fish off nightlines. Of course, once upon a time a porpoise ashore would have fed a village, and welcome. But to kill a creature for food is one thing, to kill cruelly to no purpose — that is what no other species on this planet does except us.