Roots

It’s been a pretty grim autumn. There is a constant ground bass of anxiety: over Covid, over the seeming incompetence of those who rule us, either as politicians or in the big multinational companies – who actually have more power than some nation states – and their unwillingness to tackle the one issue that unites everyone on the planet in a common cause or in a common catastrophe. Meanwhile, our culture, our media, our behaviour, seem simply to demand more bread, more circuses, more cars, and devil take the hindmost. You see what I mean? But while Advent was indeed a time of reflection on and repentance for what we and our species have done and are doing to our world and to each other it was also a time of paradoxical promise, of hope. It’s not the sort of hope that makes any common or garden sense in the usual materialist model, but then that model is palpably bankrupt and philosophically incoherent: to accept it is as much an act of faith as any religion and it is far less humane or coherent than most.

It’s been a pretty grim autumn. There is a constant ground bass of anxiety: over Covid, over the seeming incompetence of those who rule us, either as politicians or in the big multinational companies – who actually have more power than some nation states – and their unwillingness to tackle the one issue that unites everyone on the planet in a common cause or in a common catastrophe. Meanwhile, our culture, our media, our behaviour, seem simply to demand more bread, more circuses, more cars, and devil take the hindmost. You see what I mean? But while Advent was indeed a time of reflection on and repentance for what we and our species have done and are doing to our world and to each other it was also a time of paradoxical promise, of hope. It’s not the sort of hope that makes any common or garden sense in the usual materialist model, but then that model is palpably bankrupt and philosophically incoherent: to accept it is as much an act of faith as any religion and it is far less humane or coherent than most.

I start with these thoughts because without doing so you would not see why our little trip up north to what is for me God’s own country was so much a delight, so restorative, so – well, a proper prelude to Christmas and its Unspeakable Event. You see, many decades ago, in those years after WW2, an honorary uncle of mine was vicar of a parish in that lovely bit of country south of Kendal and between the Gorge of the river Kent… … where we used to watch the salmon leaping the rapids when the run was on – and the A65. That was a quiet road when I used to spend weeks each summer in Crosscrake. There stood Greatrex’ Mill, the last survivor of the five that once tapped St Sunday beck. As a child I loved going there, to see the thoughtful trout lying heads to current in the clear mill leat, to hear the stones rumble as the water turned the ponderous overshot wheel. Its paddles were green with weed, and the water broke the sunlight into a myriad sparkles as it overflowed from them. The smell of crushed oats and cut wood filled the air, and the whole road, the hedges, the lichened limestone field walls, the nearby buildings, were covered in the grey-brown dust from the milling. On the road it would hold prints of a passing horse or a line of wheel tracks.

… where we used to watch the salmon leaping the rapids when the run was on – and the A65. That was a quiet road when I used to spend weeks each summer in Crosscrake. There stood Greatrex’ Mill, the last survivor of the five that once tapped St Sunday beck. As a child I loved going there, to see the thoughtful trout lying heads to current in the clear mill leat, to hear the stones rumble as the water turned the ponderous overshot wheel. Its paddles were green with weed, and the water broke the sunlight into a myriad sparkles as it overflowed from them. The smell of crushed oats and cut wood filled the air, and the whole road, the hedges, the lichened limestone field walls, the nearby buildings, were covered in the grey-brown dust from the milling. On the road it would hold prints of a passing horse or a line of wheel tracks.

I had always promised I would take My Lady to that place where I remember a child always happy, when every day was summer. It’s a place most people would find but ordinary; but to me, in memory, it was edged with glory. It’s a little country, little, steep, green drumlin hills, sweet as the hazel nuts in its hedges. St Sunday Beck chatters along, cutting into the drumlins here and spreading itself into shallows there as it meanders along, a stream running out of a child’s Paradise. I had been back, by myself, in the intervening decades, before we met, to find little change save for the draining of the canal just past the bridge under which I used to catch summer minnows with a rod made of a hazel stick uncle Alec had cut from the hedge, a length of black cotton, and a bent pin for a hook, with a wriggly red worm on it. Oh, and the hedges of the deep lane down which a little me went to school, had got somehow lower.

I had always promised I would take My Lady to that place where I remember a child always happy, when every day was summer. It’s a place most people would find but ordinary; but to me, in memory, it was edged with glory. It’s a little country, little, steep, green drumlin hills, sweet as the hazel nuts in its hedges. St Sunday Beck chatters along, cutting into the drumlins here and spreading itself into shallows there as it meanders along, a stream running out of a child’s Paradise. I had been back, by myself, in the intervening decades, before we met, to find little change save for the draining of the canal just past the bridge under which I used to catch summer minnows with a rod made of a hazel stick uncle Alec had cut from the hedge, a length of black cotton, and a bent pin for a hook, with a wriggly red worm on it. Oh, and the hedges of the deep lane down which a little me went to school, had got somehow lower.  They were still thick with holly and ash, hazel and hawthorn, and wild gooseberries, and probably still have the sweet pignuts I used to dig up and chew, scrabbling the turf of herb Robert and campion and vetch and sweet grass aside with my blunt penknife. And the wild strawberries in season…

They were still thick with holly and ash, hazel and hawthorn, and wild gooseberries, and probably still have the sweet pignuts I used to dig up and chew, scrabbling the turf of herb Robert and campion and vetch and sweet grass aside with my blunt penknife. And the wild strawberries in season…

So, a spare day, a frosty December morning, scraping the ice off the windscreen in the dawn dusk, and then a luminous sky behind Ingleborough heralded a most perfect day we had no right to expect, a grace abounding. The sun edged every damp leaf and twig and stone with a fleeting brilliance of glory as we walked past. We parked by St Sunday Beck, by the bridge just before the vee of cottages flanking the way that led to the stone paved path, once railed, beside the busy, noisy water rushing under the dark tunnel of Stainton Viaduct.  As the beck leaves the sunlight it passes under the vaulted stonework, always damp with the slow percolation of the canal above and dotted with miniature stalactites of precipitated calcium carbonate. It sings in the cool echoing gloom beside the cobbled path. You can’t help thinking of the men day after day who tramped along it in their noisy nailed clogs to get to work at one of the mills, and then, like us, coming out to see the world all before them in the light.

As the beck leaves the sunlight it passes under the vaulted stonework, always damp with the slow percolation of the canal above and dotted with miniature stalactites of precipitated calcium carbonate. It sings in the cool echoing gloom beside the cobbled path. You can’t help thinking of the men day after day who tramped along it in their noisy nailed clogs to get to work at one of the mills, and then, like us, coming out to see the world all before them in the light.  Some of them would have lived in the cottages beside the stream a few yards back: now expensively converted, with gardens that only grow cars now, when I knew them my uncle the Vicar and his wife, often with a very young me in tow, used to visit with tactful little gifts to help the people out. For these were really poor people, and the houses, built on a useless bit of wet land, used to flood when the beck was in spate. I was a bit afraid of their dogs, which barked at me, and one of them, a lurcher, was almost as tall as I was.

Some of them would have lived in the cottages beside the stream a few yards back: now expensively converted, with gardens that only grow cars now, when I knew them my uncle the Vicar and his wife, often with a very young me in tow, used to visit with tactful little gifts to help the people out. For these were really poor people, and the houses, built on a useless bit of wet land, used to flood when the beck was in spate. I was a bit afraid of their dogs, which barked at me, and one of them, a lurcher, was almost as tall as I was.

One memory is golden enough for all. I went down there on my small own one day, and as I came out of the tunnel into the summer sunlight, there, in the pool into which the stream fell, was Frank the heron fishing. He took off with the slow flap of his great wings, his long legs straight behind him, as he saw me. I stooped and took my shoes off and dangled my feet in the water and let the little trout nibble my toes — or I like to think they did. This was one foot in Eden, indeed.

In Stainton, there is a little humpback packhorse bridge just wide enough for a pony’s delicate tread, with a parapet low enough for the packs on its back to clear the masonry. And there was the ford, always exciting to me and in wet weather even more so, nearly too much for the Vicar’s Morris 8. It had to take it at a run before starting up the hollow lane on the hill on the other side, just wide enough to take it. (But you would not meet anything coming down.)

In Stainton, there is a little humpback packhorse bridge just wide enough for a pony’s delicate tread, with a parapet low enough for the packs on its back to clear the masonry. And there was the ford, always exciting to me and in wet weather even more so, nearly too much for the Vicar’s Morris 8. It had to take it at a run before starting up the hollow lane on the hill on the other side, just wide enough to take it. (But you would not meet anything coming down.)

I had told Rosanna about the first hill I ever climbed, the one I could see from the stairs window at the Vicarage, and I have written about it in one of my books – there’s a long section on The Helm in Crossroad, which will be published by Darton, Longman and Todd in Spring 2022 and please do look it up. (In fact, there’s a much longer description of Crosscrake and neighbourhood as it was in Between the Tides: A Lancashire Youth, Beaten Track Books, 2016). It’s a wee hill as hills go, but it was special (and huge) to a five year old me, even though I didn’t know then about its hill fort. So I took her up it, and we sat on the top in the sun looking at the sun gleaming on the wide sands of the distant estuary, and down on the busyness of Kendal, and ate pork pies from our favourite pie shop in Skipton, which run close those of the late lamented Brennand’s in Finkle Street, Kendal.

Several dogs came up, bringing their owners for a walk in the sun and air, and gathered round, as they usually do. But the place was, well, busy – you could tell from the paths worn through the grass – and we wanted to be quiet. So we wandered down through the dead bracken, stopped for a brief drink at the Punchbowl where my father used occasionally to go, and back to the car. It had been a golden visit, and My Lady can now glimpse what made a younger me tick – just as when we went together to the Hochpustertal in the Dolomites, which she had known in summer every year as a child, and I had only known much later in time in deep winter, her memories were grafted onto mine.

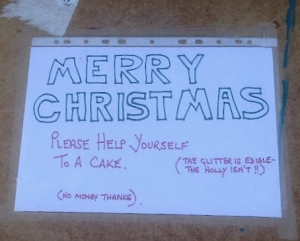

And one final joy awaited. Walking back from Crosscrake down the tiny lane to the ford at Stainton, we passed the little cottage – I think it used decades ago to be Mrs Minshull’s – by the bridge. Outside its wall was a box, firmly lidded, with a notice:

A neighbour told us the story. This man’s parents had had a confectionery shop in Finkle Street (whence all good things used to come) and worked as a chef. He made cakes for sheer delight, and shared that delight. We took one, and left a note regretting that he would not allow us to pay for it, but telling him that this blogpost would be written in gratitude for his Christmas gift and charity, a reminder that as well as the villains and rogues, the world is also full of good and generous people. I hope he reads this.

His cake was delicious, and the giving of it even more so. Some sort of symbol there?